Family History

William P Egan

19th August 1924

Life in Muttaburra in the 1930s

Muttaburra was my home for at least eighteen years of my life and it is something I do not regret. We lived through good times and some bad times and being poor seemed to be everyone’s lot, especially during the depression. Even people on the land suffered. They used to tell the story about when Stan Slotkowski got married he sent in the weekly grocery order to the Agent at Longreach and they wanted to know why it was double the usual lot. When he informed them they told him he would just have to share the usual order. Before he died I used to bring Ross Knight here for an occasional lunch and he told me once that his parents had packed to leave at least four times and walk off the property but the Bank insisted they stay so they would not have to pay a Manager. Audrey Anderson died not so long ago and until then lived at Coorparoo. Before he died, we used to meet Dr Arratta and his wife at Southport at Church some weekends. We used to spend a lot of time near Budd’s Beach at Surfers Paradise when the children were young and before they started high school. They were nearly as poor there as what they were at Muttaburra and Mrs Arratta told Patricia once that if it was not for his occasional locum they would barely exist.

When I was growing up in Muttaburra they were halcyon days. There were few motorcars and it was, if isolated, a close-knit community. Pat Haseler, Jim Walker, and the three Scott brothers were all part of the local football team and the Crombies and the Dowlings were main players in the local cricket team. There were tennis tournaments, basketball teams and of course the racing. There were grass-fed and corn-fed meetings and the usual Balls when the travelling caterer used to arrive for the race meetings. My Mother was always going to Saturday afternoon C.W. A. cutting up preparing sandwiches by the tubful for some dance or function that evening for their supper. Mum played the piano for most of the dances but at race time it was usually Carter and Pope from Longreach. Carter played the piano and Pope played the trumpet. J Y Shannan was involved with amateur racing and always brought a horse or two to Muttaburra. Brookwood played a big part in the racing. I can remember when the Brookes family visited the property before the War they always paid a visit to the school. They provided us with sporting equipment and on one occasion their son who was about twelve or thirteen showed us how to fly model planes and left us kits to assemble the rubber band type.

One of the social events of the year was the fancy dress ball and Mrs. Hall played a big part in organizing it. After school everyone who was partaking had to assemble at the hall for Grand Parade practice. I can still remember the music that went with the parade. There were singles, doubles, fours, and sets. I can recall I was once in Mrs. Hall’s set as a cricketer. There were always lots of female fairies and male swagmen. What they were going to appear as was a well kept secret and there was always disappointment on the night when the prizewinners were announced. Some Mothers slipped the judges a special prize to be awarded to their child to keep the peace. Mrs. Hall also organized the school breakup concert and it was held in the open-air picture show. On one occasion it poured rain an hour before the show and swamped the stage. The show had to be postponed until the following Saturday and by that time it was holiday period and the kids were not that interested in performing at that late date.

Tom Hall ran the silent picture theatre and Aunty Madge McCarthy played the appropriate music to accompany the silent movie. Tom Mix was everyone’s favourite and when he appeared on the screen there was always a very vocal audience. When it came time for Tom to start shooting the baddies there was always some wit who had saved a paper bag to create the big bang. Eventually travelling talkie shows played there and that was the death knell of silent films.

George Lake operated the family soft drink factory, which was located up next to the Catholic Church. I sometime helped him wash the bottles and label the finished product. My reward was usually my favorite of a bottle of creaming soda. George liked his pot of beer, and spent a lot of spare moments quaffing at Queenie Fahey’s Australian Hotel and paid for it in cases of soda water. When credit started to decrease George would be seen making for the factory to produce some more credit as quickly as possible. The soda water was produced in the bottles with the marble in and George had a good supply. Queenie was Mrs. Bill Spence’s, Culloden sister.

You probably learnt Longfellow’s poem The Village Blacksmith at school. Our blacksmith’s shop was opposite the Mt Cornish Hotel on the corner and I have been told Sam Clemesha came to the town with two shillings and sixpence and started his first business there. There was no spreading chestnut trees, but we used to look in at the open door on our way home from school. Sometimes the blacksmith would let us pump the bellows while he fashioned a horseshoe on the anvil. With the arrival of the motorcar the building became a garage and at various times a mechanic would operate from there. Most of them were self-taught and knew little or nothing about combustion engines. Behind the building was a small mountain of blacksmith’s tools and I often wonder what became of them.

At school the Protestants always had religious readings on a Friday morning. As the Catholics were taught Sunday school at the Church they indulged in some other activity during reading time. Mrs. Hall taught Sunday School and Dr Arratta was always the alter boy when the Priest visited from Barcaldine. Their interpretation of Religion still haunts me today. I can remember one visiting Priest exhorting the congregation to cough up their money and if they put a three-pence on the plate it would be on their seat the next time he visited. How he would know where anyone sat I don’t know. The good Doctor was at one time going to teach me Latin so that he could retire from the job. As I showed little interest I think the idea was abandoned.

The annual gymkhana was a popular event and if I remember correctly it was usually held up near the dam. There were pony riding, bike races, foot races, swimming, and billy goat races. The Dicksons usually won the billy goat races, as they seemed to come most prepared for the event. As I was not such a wonderful swimmer I used to find it a long way across the dam especially if it was full. Everyone had a good time.

Between our house and Little’s place used to be a bore drain and on the footpath it was crossed by a little bridge. Until the mid 1930s when the old water main was replaced there was an outlet, which ran continuously to alleviate the pressure on the old main. The water flowed towards the rubbish dump and eventually into the Landsborough Creek which kept the waterholes filled. There was a swamp on the way, which was not only a watering place for local cows and goats but also attracted at times flocks of wild ducks. Tim Little would be out with his shotgun and on many occasions we were treated to roasted duck for dinner. Mrs. Little was my Mothe’s sister. It was not unusual to see travelling mobs of sheep watering along the bore drain.

On a Saturday morning my brothers and I and other boys spent the morning Cray fishing at the creek and sometimes we caught so many Mother had to cook them in the clothes boiler. A crayfish dinner with hot scones and butter was something I remember and in season fresh radishes, tomatoes and lettuce were added from my Father’s garden. Other times we went to the Pump Hole to fish for yellow belly. Today I can’t stand the taste of them as I find them too oily.

Fong Sang was the local baker for many years and bread was sixpence a loaf. He made very good bread and it was rumoured that he used to knead the dough in the bin at night by using his bare feet, nobody ever complained about the quality of his bread. He invested a lot of his saving in silk mills in China and when Japanese invaded that country in the thirties he lost heavily.

Kum Sing owned the garden at the edge of town. He grew lots of different vegetables and also had an orchard of oranges, lemons, and mandarines. He also grew grapes and around New Year’s Day there was always a picnic at the Broadwater. For two shillings he would fill a kerosene tin full of grapes, as his contribution towards the picnic. When he died he was buried in the local cemetery but was exhumed a couple of years later and his remains returned to his family in China. His remains showed signs of his habit of smoking opium but I think everyone locally was aware of that. He had an assistant called Jimmy Joe [that was his name] and he used to hawk the produce around town with a horse and dray. I can remember my Father liked shallots and they were three-pence a bunch. One day Jimmy turned up at my parent’s home in a disheveled and distressed state. Apparently when he saw my Mother he was overwhelmed with joy. Five days earlier he took a shotgun to chase a wild pig that had broken into the garden and during the chase he crossed the creek. The pig disappeared and then Jimmy became disorientated and could not find his way home. He wandered around the channels for five days without food until he stumbled across the road, which led him back to town. My Mother fed him tea and cake until he revived enough to proceed home. His partner had not even reported him being missing. Along the way he had dumped the gun so it is probably still lying near the Thomson River somewhere.

As my Mother played the piano, our home was a meeting place for young people for singsongs and we had some very good singers at times. She also taught local girls the piano. I don’t think any of them became concert pianists. None of us ever learnt the piano as I think the small fee my Mother received helped keep the wolf from our door. I was ready to learn once but I think the paying customers were more important. When my Mother moved to the Pioneer Hostel at Longreach I arranged for her piano to be delivered there. I left it there when my Mother died in October 1988. Apparently she still played it up to a few weeks before she died.

Christmas time was a festive one. We did not receive many presents but it was a time for eating. We always had a couple of suckling pigs fattening in a sty and as Littles had cows we seemed to always have a supply of separated milk besides fresh cream and home made butter for ourselves. There was always turkey, which we kept, and chook and a leg of ham. There was ample ginger beer and brewed horehound which was our specialty. No liquor was allowed in the house except rum to make the Christmas cake. Dad was fond of a drink; he was allowed to finish the bottle off. It was his privilege on Christmas day to toast the King before Christmas dinner, which at times was eaten in the middle of the day when the temperature was well over the one hundred degrees mark. It is probably why we are Monarchists today. On one occasion my Father went away somewhere and returned home with an ice-cream churn, which he had bought along the way as a homecoming present. I remember he brought it home full of sweets. I have not seen one like it since, even in a museum. It was about a two-gallon metal cylinder approximately twelve inches across and had pressure lids at both ends. At one end was an insert cylinder, which held about a quart of custard, and the other end was filled with ice and coarse salt. It took about four hours to make the ice cream. It was before the days of refrigerators but Andrew Cassimatis was our source of supply for ice for our operation. All perishable food was kept in a large bag cooler and so was the horehound to keep it from exploding.

Mrs. Wilson’s Royal Hotel was the meeting place for most sportsmen. Her two sons Joe and Bert were keen sportsmen. Bert was killed in Syria during World War II. At one time they held buckjumping contests in the horse yards behind the hotel and I can remember once her son-in-law Mr. Kennedy playing the bagpipes one evening during the event before he died at an early age.

Klugh and Samuels were a familiar name in the town and owned the main street. From what I have learnt of these two gentlemen they were investors who bought large blocks of land and eventually sold them as house blocks. After the Civil War in the USA land grabbers from the North descended on the South, bought land at minimal prices, and resold it later at a huge profit. The last owner of the shop that I can recall was Jas Roberts who although well liked in the town, apparently was not a very astute businessman. I can recall when I was small my Father would take me there and buy me a pennyworth of boiled sweets. Jas would meticulously make a cone out of newspaper and fill it with the sweets. His bookkeeper was Jas Brannelly who lived with his family opposite us. I don’t know the circumstances but Andrew Cassimatis arrived with a Bailiff at opening time one morning and announced that he was now the mortgagor and demanded the keys. He promptly sacked the owner and bookkeeper and took over the business. Times were changing and the business never prospered afterwards. The Brannelly family were good neighbours and they and their family of a teenage son and two daughters were devastated by the events of that morning. They soon left for Rockhampton where they spent the rest of their days.

Sam Brown [name changed to protect the family] was a good man but sometime not so good as things unfolded. As a young teenager I sometimes went fishing with him and also chased kangaroos. He had two dogs and a rifle and I had a .22 rifle. One day we were on the northern side of the reserve when we spotted a large kangaroo. Sam shot the animal and wounded it then sent the dogs after it. We lost all sight of the quarry and dogs, which eventually returned. I do not know how it happened but we somehow got into the back of Bluegate, which belonged to the Lloyd family. We came across a stray young wether and Sam caught and killed it. He put the carcass and skin into a bag, which he carried and promptly headed for home. When I returned home I told my mother what had happened and that I had been offered some mutton. She became furious and told me in no uncertain terms that if I ever brought stolen meat home she would kill me or have me sent to gaol. That was the end of my association with Sam.

He related this story to me when I was home on leave once after I joined the Airforce. When the Japanese came into the war Sam was working both at Verastan and Tragowel at different times. He was married, his wife and couple of young children lived on the stations with him, and I suppose he had to pay Scott or Seaton for the meat he and his family consumed. It must have been early in 1942 that Sam went looking for a kangaroo to shoot one weekend. He crossed the boundary into Brookwood territory and the only thing he could find was a small flock of young wethers. There was a cheep supply of meat so he shot one of the animals and was in the middle of skinning it when on the horizon appeared Noel Bowden on horseback and he worked at Brookwood.

Sam was about to be caught red-handed stealing a sheep and he hid behind a tree, as Noel had not yet seen him. Noel was still coming his way and the situation did not look too good for Sam. To cover his presence he started firing volleys from his rifle over Noel’s head and he promptly turned around and headed back to the station at full gallop. Sam took the advantage to escape so he collected his booty in the bag and hotfooted it for home.

Noel got back to the station in a terrified state he told the Manager that he had been attacked by a group of invading Japanese who were firing guns at him. The police were called and an armed posse gathered to go out and meet the invaders. No trace could be found of the enemy and after a long search everyone went home to leave poor Noel to suffer his guilty conscience. All this time Sam and his family were sitting down to a roast dinner.

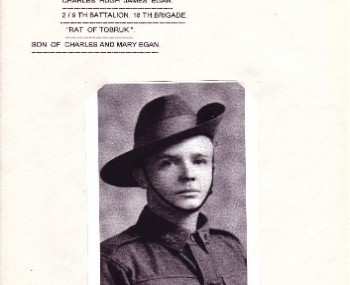

War Experiences

My brother Chas joined the Army in 1939 shortly after war broke out. He was six years older than me and on his final leave before he sailed in 1940 his parting words were that the war would be over in six months and for me to stay home and care for our parents. How wrong he was. He left Australia shortly afterwards and disembarked at Glasgow where he and others from the ship went straight to hospital with mumps. After a short stay in Scotland he rejoined the 18th Brigade at Colchester in England where he learnt to become a Bren gun carrier driver. If they had arrived in England a few weeks earlier they would have been caught in the Dunkirk debacle. By Christmas time that year he was back in the Middle East where he was his first action against an Italian fort in Libya where he was wounded in both hands by an Italian shell, which landed in front of the machine gun he was operating on the ground. Apparently it was not until he went to Tobruk that he received his first carrier and even there he went on patrol on a motor vehicle as infantry at night. His vehicle hit a land mine one evening and he finished up in hospital with shrapnel wounds all over his body. After months of being trapped by Rommel’s army his Brigade was eventually evacuated to Syria by British warships where they rested before returning to Australia.

After a short home leave his Brigade went to Milne Bay in New Guinea where, with the help of a detachment of U.S. Marines they stopped the invading Japanese in their tracks. It was found that the carriers were useless for jungle warfare so instead of going back to the infantry he and some of the old originals joined the New Guinea administration where they spent the remainder of the war recruiting native labour.

I enlisted in the R.A.A.F in August 1942 when I turned eighteen and was summoned to Brisbane in early March 1943 for an interview and medical check up. At the recruit centre in Creek Street the first person I met was Howard Foster who had been a schoolteacher at Muttaburra during 1937 and 1938. We knew each other well and were pleased to renew our acquaintance. He had been in the R.A.A.F over two years and had been in a plane, which the Germans shot down in the Middle East. One of his legs was badly injured and as a result he had been grounded and because of his education qualities had been made a Recruiting Officer. It was my ambition to join the Aircrew but he assured me that none of the intake would be sent for training because the facilities were stretched to the limit. As a compromise he suggested that as I knew something about storekeeping he would send me to the stores department and perhaps later I could reapply for aircrew. I spent the rest of the war as a storekeeper which when I look back now and know how many of my young friends lost their lives over Europe it is a sobering thought that I am still alive.

After months of training at Maryborough I was sent to the Stores Depot opposite the old museum in Brisbane, which was alongside the railway line near Bowen Bridge. My home for the next twelve months was Grangehill on Gregory Terrace. You can imagine how I felt going from Muttaburra to live in a glorious old stone mansion that had been built by the Raff family in the nineteenth century. Life was good there and after work except for Monday night we could come and go as we pleased. Only those men who came from outside Brisbane lived there and the rest went to their homes each night. One of my roommates for a time was Hugh Sawrey the artist. We were the same age and he came from the bush but in those days he did cartoons for the Bulletin and was paid a handsome two guineas if any were published. City life was good and quite often I went to the Races on the weekend. There were a few clubs and always a dance to attend and occasionally a party at a private house in the suburbs.

Neville Bullen was stationed at an Army AckAck unit at the other side of Victoria Park and I can recall he invited me to a unit dance there one night. I enjoyed the dancing but for most of the evening Neville seemed to be surrounded by a bevy of attractive young A.W.A.S. who were stationed there. He and I visited a girl in the Hospital a couple of times. She came from the west but I don’t remember her name.

In June 1944 I was posted North to the tropics and spent the remainder of the war under canvas in the area. After some time in Townsville forming a mobile stores unit I eventually left for the Halmaheras in early March 1945 where the unit stayed for two months as guests of the U.S. Fifth Air Force. Just south of the island on Ternate is an active volcano and today it is still used as a navigation aid for aircraft. The islands were sparsely populated then but with the transmigration system in Indonesia they must have sent a lot of people from Java to them during the past fifty years because that is where Moslems and Christians are murdering one another today. They would have depended on supplies of rice from Java for their main food source because I don’t think anything but a few pawpaws and coconuts would grow there. It was at this island that I met Sid [Darky] Cuddy who was in an Airforce hospital recovering from appendicitis. One day we decided to go looking for pawpaws, which grew in huge clumps, and the only way to get one down was to chop the tree down. They grew very spindly and tall and the clumps were nearly impenetrable. We walked for quite a while and found no fruit so we decided to return to camp. We could see the other side of the island across a swamp about fifty yards in width so we decided to wade across and make our way back along the beach. The water was up to our waists in places but as it was hot it did not worry us. When we got to the other side we were in the back door of an American Army camp and they were horrified when we told them the way we had come. For some reason they used the swamp as a buffer between them and the perimeter which was only two hundred yards away. We knew that an American Negro battalion was camped along the perimeter to the other side of the island. They had come from somewhere else for a rest and as camping areas were at a premium they just put up their camp and had machine gun pits every so many yards apart and anything that moved within half a mile beyond there did not have a chance to survive. There were a couple of hundred Japanese who had retreated to the hills beyond and they were glad to stay there until they surrendered when the war ended in August. Apparently they were in pretty bad shape from lack of food. I had traded with some of the Americans and all of their clothes were dyed jungle green. They liked our white towels, which they sent home to the families for gifts. I looked after the section, which carried nails, screws, nuts and bolts, and other building materials. Nails were good trading currency and our C.O. knew that anything that was traded went into the unit slop chest for equal distribution. Our Unit comprised of no more then sixty personel and everyone liked the C.O. who was a bachelor and Permanent Air force from the pre-war. Nails were a scarce commodity, and a fifty-six pound case was worth a carton of ten thousand cigarettes. Our favourite food was their canned chilli-con-carne and we had cases of it, which the cook would serve on toast for breakfast.

Towards late April we discovered the Westralia was docked at the wharf so Sid and I went one Sunday to visit Allan Langdon who was one of the crew. They were loading A.I.F. troops who had recently arrived from Australia and they were being transported to Tarakan Borneo for the invasion. My unit was already packed but we did not know when we were going to leave. After we had dinner with Allan we both left to return to our units. There was plenty of traffic on the only road so we had no problem getting a ride back to our camps. When I arrived back at my camp I leant that some of our Unit had already left to board the Westralia, so I asked the C.O. if I could join them. He told me they were a small crew sent along to erect the tents, if and when we got ashore at Tarakan and he preferred that I travel with my stores. The rest of us boarded a couple of landing crafts with our stores next day and travelled in convoy to our destination. Sid went to North Borneo early in July and I didn’t see him again until after the war ended. I had been posted back in January to a Kittyhawk Squadron as their storekeeper. I was quite contented where I was and they were somewhere south of us. It was decided that I would join them at Tarakan as they were making their way in that direction. We landed in early May and I joined them when the planes arrived in mid July. From May to the end of June it took that time to build the airstrip and everyone except cooks and stores personel had to spend each day building it. According to the history of my Unit kept in Canberra I was a crack shot with the .303 and if that was so then hitting a stationary bulls-eye was easy compared to trying to shoot a fox or kangaroo on the run. For a boy from the bush it would have been easy to be better than the city bred mates.

When the war ended I had to stay and what equipment, which was not dumped into the sea by prisoners off barges, was packed for return home. I arrived back in Sydney Christmas Eve 1945 and it felt good to be back to the bright lights. Along with other stores people we were kept until May 1946 before we were discharged. We were offered promotion to join the Occupation Forces in Japan but for most of us the war was over and we wanted to go home.

The war years must have been traumatic ones for our parents and it would have been a time of joy when my brother and I returned home safely. My mother had a brother in World War 1 and he suffered from the after effects of gas for most of his life. My father had two brothers serving in France and one still lies in his grave at Leper [Ypres] in Belgium.

Life After The War –

It was time for me to get a job and return to civilian life. I eventually rejoined the Post Office and spent a number of years as a relieving clerk around the state. During that time I tried unsuccessfully to draw a block of land and as I write this I feel that it was probably the best thing that did not happen. My automatic Morse Sending Device is now in the Queensland Museum and is sent out with Educational displays to all of the schools around Queensland. I had bought myself a new car and when I tired of country service I drifted back to the City in the early 1950s, and started working in the Shipping Industry where I spent the remainder of my working days. I spent fourteen years with Dalgetys overseas shipping and when conventional shipping changed to containerization in the early seventies I had to move to that and spent a number of years as a Marketing Manager on the Japanese trade. In 1955 we were married, this house was ready for us to move into, and we have lived here ever since. We have two sons and a daughter and then Patricia resumed her Children’s Dentistry, which she had practiced visiting schools all over the State before we were married.

After the children finished their education and eventually were married Patricia and I took the opportunity to do some travelling while we were fit and able. We have travelled to many countries in Europe and some in Asia.

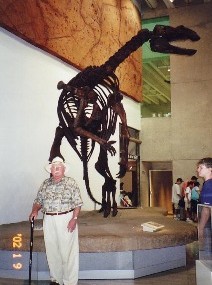

In recent years when I present my Passport at the immigration Counter at the Airport I have watched closely to see if there was any reaction on the Officer’s face when he reads my place of birth. An odd one has given me close scrutiny but none have ever asked if I was related to the Dinosaur.

I have written what I believe will give you some idea of life at Muttaburra. If my writing has upset anyone then it has not been my intention. It is like writing up one’s genealogical history. You can write what suits you but when the certificates are produced then the facts have to be recorded correctly.

Extracts from a letter from William P Egan, 24th July 2000